Pulsara Around the World - February 2026

January Recap The start of 2026 was on the slow side for our events schedule, with our team heading to the Florida Fire & EMS Conference, the...

4 min read

Team Pulsara

:

May 23, 2024

Team Pulsara

:

May 23, 2024

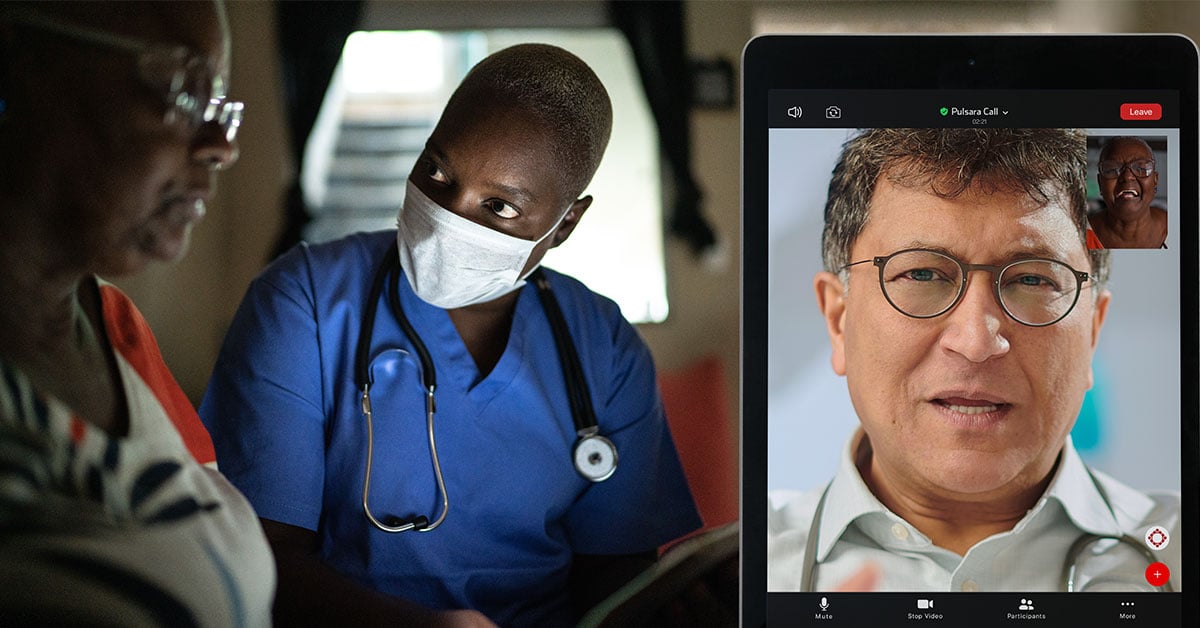

During major emergencies like earthquakes, floods, or mass shootings, health resources can quickly become overwhelmed, causing breakdowns in communication and coordination. Hospitals may reach capacity, leaving some patients stranded without adequate care and making it difficult for family or friends to locate them. These issues are exacerbated in large-scale incidents affecting entire regions or states.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Texas faced these challenges but improved their emergency healthcare response by implementing new systems and technologies. Texas's success largely hinged on Regional Medical Operations Centers (RMOCs), which coordinated efforts locally and regionally. Eric Epley, Executive Director and CEO of the Southwest Texas Regional Advisory Council (STRAC), highlighted how Texas managed load balancing through RMOCs and enhanced communication systems, with Pulsara playing a crucial role in ensuring optimal patient care statewide.

The following is an excerpt from an article by John Hick, ASPR TRACIE Senior Editor. It was originally published in The Express on HHS.gov in February 2024. Read on for an excerpt, and check out the full article here.

_____

Regional patient load balancing is an art and science that has evolved across the U.S., particularly over the past few years. ASPR TRACIE interviewed Eric Epley of the Southwest Texas Regional Advisory Council— who was the Council’s first official hire in 1998 and currently serves as the executive director/chief executive officer (CEO)—to learn more about how the Council has evolved and promising practices in load balancing and other trauma-related efforts.

The Texas Trauma System was created in 1989 by the Omnibus Rural Healthcare Rescue Act, which directed the state’s public health authority “to (1) develop and monitor a statewide emergency medical services (EMS) and trauma care system, (2) designate trauma facilities, and (3) develop and maintain a trauma reporting and analysis system” to, among other things, monitor the system and provide statewide cost and epidemiological statistics (Texas J RAC Advisory Council, 2016; Legislative Reference Library, 1989). The state was divided into 22 regions (i.e., Trauma Service Areas, or TSAs) and Regional Advisory Councils (RACs, which are non-profit and tax-exempt) who develop regional EMS plans, provide related public information, provide a forum for EMS providers and hospitals to discuss TSA issues and network with other RACs, and track related data.

The Southwest Texas Regional Advisory Council (STRAC) was launched in 1993 and:

STRAC’s mission is to “reduce death/disability related to trauma, disaster, and acute illness through implementation of well-planned and coordinated regional emergency response systems.” Their vision is to have the “lowest risk-adjusted mortality for emergency healthcare conditions.”

While each RAC is different, the boards are generally comprised of trauma surgeons, nurses, hospital administrators, fire chiefs and paramedics. There is also a requirement for there to be at least one Level 3 designated Trauma Center in each TSA; most TSAs have a Level 2 or Level 1.

"When you have a high-functioning day-to-day regional trauma/emergency health care system, your disaster response will be better. It’s like a vaccination for disasters. If it doesn’t work well on a daily basis, it is not going to go well on disaster day."

— Eric Epley

John Hick, ASPR TRACIE Senior Editor (JH): How are communications handled within the region and around the state, and how has this changed over time?

Eric Epley (EE): In 1994 there were three Level 1 Trauma Centers in the region: Wilford Hall Medical Center (run by the U.S. Air Force, and now Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center) Brooke Army Medical Center (BAMC, run by the U.S. Army), and University Hospital. All three of them went on diversion frequently and trauma patients were getting stranded in rural hospitals. The county leadership convened a task force to address these challenges. Working as a flight paramedic at the only air medical helicopter agency in the region at that time, I attended the task force meeting with my boss (a retired army colonel), the county judge, hospital chief executive officers, and trauma medical directors to figure this out. Our primary goal at the end of that meeting was that no patient should ever be stranded in south Texas. To achieve this, we agreed we needed a “one call” center with an operator who could track the request and follow up with trauma centers to ensure patients received a destination in a timely manner. This is when I was assigned to manage what we named “MEDCOM,” which was created to serve as a call center and handle patient transfers to one of the three trauma centers following the agreed-upon distribution plan. We have grown and overcome several challenges over the years. We found that having what I refer to as “final decision makers” (e.g., hospital chief executive officers and fire chiefs) in the room will get us to a decision relatively quickly. We do vote at STRAC, but we have never had a non-unanimous vote; we make decisions via consensus. We are looking for a win-win or a no deal; there is no in-between. What’s best for the patient (not the hospital administrator, fire chief, surgeon, or nurse) is our guiding mission.

JH: Have you broadened your service to include other time-sensitive emergencies?

EE: Although STRAC has offered and at times advocated for this, we have not transitioned to using MEDCOM for cardiac and stroke patients. STRAC does have multiple related committees (cardiac, stroke, pediatric, mental health, etc.) which set clinical guidelines and work on common protocols and processes, but MEDCOM only handles interfacility critical trauma transfers. We also manage the air medical traffic coming into San Antonio. With 15-20 aircraft in the region, Saturday nights can look like a beehive in our medical center area. Most hospitals can only put one helicopter on their pad at a time. They all call MEDCOM when they’re 15 minutes out to tell us where they’re headed, then five and one minutes out, and upon landing. This has greatly decreased confusion among the hospitals and air medical providers. So, STRAC serves as a consensus-building organizer and coordinator for all time-sensitive emergencies, but during routine operations, MEDCOM only coordinates critical trauma transfers. This changes during a large-scale event. Following September 11, 2001, for example, we developed our concept of the Regional Medical Operations Center (RMOC). Our RMOC (which is critical for managing large-scale, time-sensitive emergencies) is based on MEDCOM, and we first used it in the response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

![]()

For more from Eric Epley on tackling challenges in crisis response, check out the instant replay of our webinar Streamlining Crisis Response: A Deep Dive Into MCIs And Large Events.

January Recap The start of 2026 was on the slow side for our events schedule, with our team heading to the Florida Fire & EMS Conference, the...

Recent research shows how Pulsara was successfully leveraged to connect more than 6,000 COVID-19 patients to monoclonal antibody infusion centers via...

At Pulsara, it's our privilege to help serve the people who serve people, and we're always excited to see what they're up to. From large-scale...