Baker to Vegas: Leveraging Pulsara to Manage a Planned Event

Although they have the advantage of prior awareness and preparation, large-scale planned events pose unique challenges for emergency management...

11 min read

Team Pulsara

:

Oct 09, 2020

Team Pulsara

:

Oct 09, 2020

![Roundtable Discussion: The Future of the EMS Profession [2020 EMS Trend Report Part 5]](https://www.pulsara.com/hubfs/medics-amb-radio-1200x630.jpg)

EDITOR'S NOTE: EMS1, Fitch & Associates, and the National EMS Management Association recently released their third annual EMS Trend Report, proudly sponsored by Pulsara. Because the articles and advice found within contain such critical subject matter, we've elected to publish each segment one at a time here on our blog. This excerpt is from Roundtable: Mapping Alternative Destinations and a Career Path for EMS, the fifth entry in the 2020 Trend Report. Read, enjoy, share, and take to heart the following information brought to you by the most prestigious thought leaders in EMS.

The fifth annual EMS Trend Report explores how recurring and emerging trends are impacting prehospital medicine. We asked industry experts to analyze how the results reflect current healthcare trends, what they mean for EMS post-COVID-19, and how they can guide retention efforts.

The panel includes:

|

|

|

|

|

Maria Beerman-Foat, PhD, MBA, NRP |

Chris Cebollero |

Catherine Counts, PhD, MHA |

|

|

|

|

|

Maia Dorsett, MD, PhD |

David K. Tan, MD, EMT-T, FAAEM, FAEMS |

Matt Zavadsky, MS-HSA, EMT |

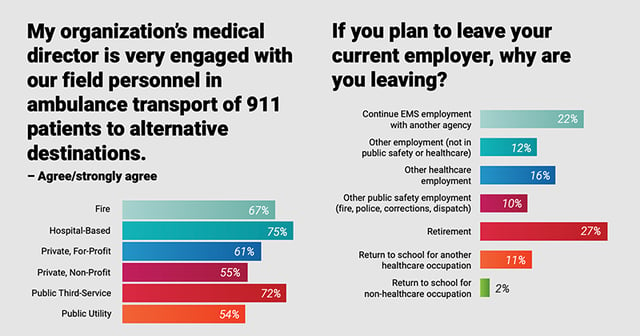

Beermann-Foat: I was most surprised by the question pertaining to medical director engagement. While alternative destinations have been an area of discussion for several years (especially due to hospital over-crowding), I was pleasantly surprised to see nearly two-thirds of all respondents selected that they agreed/strongly agreed their medical director was engaged in ambulance transport of 911 patients to alternative destinations. Hospital- based systems reported the highest engagement in this area, closely followed by public third-service models.

This made me wonder if this was because hospital-based systems are essentially able to keep the patient under their umbrella of care, though the patient isn’t being transported to their emergency department. In other words, the hospital system may be able to continue billing the patient for additional services beyond the initial ambulance transport, thereby not “losing” revenue from the non-ED destination. Whereas in other types of systems, the alternative destinations do not necessarily contribute toward the organization’s bottom line beyond the initial transport.

Cebollero: One thing that stood out for me was the percentage of individuals who are looking to retire. The age-old question comes to mind, is EMS a career or a steppingstone? Are we finally turning the corner, in that more individuals are making EMS a career they can retire from?

On the clinical side, the amount of TXA adoption (31% across respondents, highest in hospital based services – 45% and public third-service models – 39%) was surprising. Is this the next wonder drug that everyone is getting on the bandwagon, and will it continue to have an impact in the future? We shall see.

Dorsett: When asked what the most critical issue facing EMS today, the one choice that appeared in the top three of all demographics was retention of personnel, above and beyond public perception, integration with healthcare, and quality of care, which did not make the top three of any subset of EMS professionals.

I think that this is an example of focusing on the symptom rather than the disease. In reading the answers to the question, “If you could recommend to policymakers and the public one thing that would improve the current state of EMS, what would that be?”, many of the responses focused on recognition of EMS as essential healthcare providers within the system, with wages, benefits and respect commiserating with their expertise. I would argue that the critical issues are actually the interrelated root causes of our lack of retention of the EMS workforce.

Tan: As an EMS medical director, the finding that caught my attention was the obvious disconnect between medical directors and field personnel when it comes to perceived levels of engagement, and it was a major disconnect! Seventy percent of the medical directors felt like they were engaging field providers, whilst only 21% of those providers felt engaged. I think this represents a major opportunity for the physicians to improve their relationships with their surrogates in the field.

Closing this gap would undoubtedly have clinical implications for improvement. In those agencies where the medical director is felt to be more engaged, for example, there was a positive correlation with the belief that they were better prepared to address a pandemic. This is especially timely information in the age of COVID-19. When medical directors actively participate in the training and evaluation of their crew members, I cannot help but believe it improves overall crew performance and care.

Zavadsky: The finding that “retention of quality personnel” ranked first, second, and third as the three most critical issues facing EMS today for field providers is exceptionally concerning. The survey also found a 10-point decline in the willingness to recommend EMS as a career for providers with five or more years’ experience. Clearly, field providers feel that career longevity is a threat to the future of our profession, and they are less than willing to recommend it as a profession.

Other survey findings seem to paint a rosy picture for EMS’ future and the recent COVID-19 pandemic has brought a lot of attention to new value propositions for our profession. But, we need a strong foundation upon which to build the EMS delivery model of the future. Leaders need to focus efforts on finding ways to improve employee satisfaction and sense of worth in the organization to keep them.

Beermann-Foat: Recruitment and reimbursement continue to be areas of focus and concern across the profession. Without having performed a Pareto chart to see where the true 80/20 principle lies among the various factors impacting EMS, my impression is that these two areas would give us the biggest bang for our buck if they were improved/remedied. Retaining experienced personnel (who have not yet reached retirement age) has the potential of improving an organization’s overall performance. More years on the street bring with them insight, wisdom and intuition that can only be achieved through putting in the time on the job. It’s a bit disheartening to see that approximately 44% of respondents in the 0-5 years of experience category have plans to leave within the next 4 years of service. Right as they’re really hitting their groove and the job skills are becoming second nature, they’re jumping ship.

Beermann-Foat: Recruitment and reimbursement continue to be areas of focus and concern across the profession. Without having performed a Pareto chart to see where the true 80/20 principle lies among the various factors impacting EMS, my impression is that these two areas would give us the biggest bang for our buck if they were improved/remedied. Retaining experienced personnel (who have not yet reached retirement age) has the potential of improving an organization’s overall performance. More years on the street bring with them insight, wisdom and intuition that can only be achieved through putting in the time on the job. It’s a bit disheartening to see that approximately 44% of respondents in the 0-5 years of experience category have plans to leave within the next 4 years of service. Right as they’re really hitting their groove and the job skills are becoming second nature, they’re jumping ship.

While reimbursement may seem like a concern for upper level managers and executives, it’s something that impacts every employee of an organization. Our ability to get paid as a service for the work that we’ve done dictates every other financial decision down the line (including providing livable wages and decent benefits). Though personnel may not have financial motivators when they enter the profession, finances often become an issue later as the cost of living increases and/or their family size grows.

Personnel should be able to feel confident that they’re going to have ambulances that

are reliable and safe, that they’ll have all the equipment that they need to perform at their provider level, and that their needs will be covered if they get injured while in the service of others. Yet, more often, agencies are having to tighten the purse strings because the cost of doing business continues to increase while reimbursement lags behind.

Counts: Physicians receiving formal training before entering the managerial space is a growing trend in brick and mortar healthcare, so it doesn’t surprise me that active medical directors are continuing to grow as the norm rather than the exception.

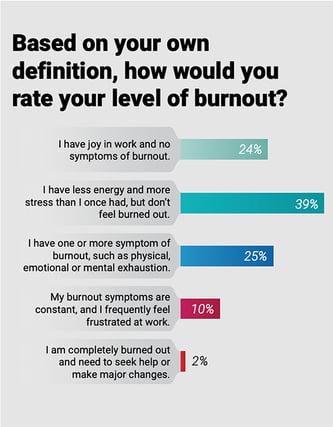

Dorsett: The prevalence of burnout remains a clear and present danger to our workforce and to the quality of patient care. More than a third of respondents reported having at least one symptom of burnout, with more than 1 in 10 responding that these symptoms are constant. Estimates of burnout amongst other healthcare providers parallel or even exceed these numbers. This not only is disturbing, it is a healthcare crisis.

Dorsett: The prevalence of burnout remains a clear and present danger to our workforce and to the quality of patient care. More than a third of respondents reported having at least one symptom of burnout, with more than 1 in 10 responding that these symptoms are constant. Estimates of burnout amongst other healthcare providers parallel or even exceed these numbers. This not only is disturbing, it is a healthcare crisis.

Zavadsky: The sections of the survey related to expanded roles for EMS seem very logical given the continued march of the healthcare industry toward value-based care. Nearly 64% of medical directors indicated that MIH-CP is the future of EMS. The COVID-19 pandemic is demonstrating to our key stakeholders that EMS is more than just 911 and a method of conveyance. EMS agencies across the country are performing patient testing and follow-up, contact tracing, navigation of 911 patients to alternate destinations, and a plethora of other roles. CMS and other payers quickly changed coverage rules to align clinical and financial incentives to prevent patients from going to the ER. Payers, hospitals, public health, and elected officials are finally recognizing we are part of the healthcare system.

Beermann-Foat: Like other times in history, people often make career entry and exit decisions based on major events. For example, after Sept. 11, 2001, the public safety sector saw an increase in the number of people leaving their established professions to join our ranks to serve the community. The pandemic has the potential to drive people toward or away from the EMS profession. Many of the difficulties we’ve encountered in obtaining sufficient levels of PPE and ensuring the health and safety of responders may serve to drive away experienced personnel and those considering entering the profession.

However, similar to 9/11, the public has come to re-appreciate the role that EMS and other health professions serve in the community. Therefore, we may see an increase in individuals interested in joining this honorable profession. It’s too early to tell which way things will go. Depending on a provider’s impression of how well their agency has adapted to and addressed the challenges the pandemic has presented, we may see experienced providers who had not planned to leave any time soon suddenly decide to leave or vice versa.

It’s easier to have confidence in a system that remains untested.

Likewise, what we deem as important can be drastically impacted by societal events. It will be interesting to see if there will be a stronger push for MIH/community paramedicine programs and telemedicine as the pandemic continues.

Counts: While our internal dialogue has shifted to provider safety, supply chain management, and – in some cases – crisis standards of care, the bigger change has likely been external to EMS. This pandemic has highlighted the value that EMS provides to the community while shining a light on the risks faced by providers in the prehospital setting. In many cases, this has resulted in increased support and appreciation from the community. Whether this translates to positive operational or budgetary changes is a later question, but the first step of recognition and awareness has come a long way in the past four months.

Internally, I worry most about burnout. EMS is already hard on the soul. When faced with the challenges that a prolonged disaster brings, we’re only going to see an increase in mental health needs. Interestingly, this survey showed that burnout is also growing among those that aren’t field providers (i.e., management). I would guess that trend will also continue, as developing new response systems from scratch in the span of weeks and months is also emotionally exhausting.

Internally, I worry most about burnout. EMS is already hard on the soul. When faced with the challenges that a prolonged disaster brings, we’re only going to see an increase in mental health needs. Interestingly, this survey showed that burnout is also growing among those that aren’t field providers (i.e., management). I would guess that trend will also continue, as developing new response systems from scratch in the span of weeks and months is also emotionally exhausting.

Dorsett: In hindsight, I think that the confidence in preparedness for a pandemic would be much lower. Reviewing the survey results, about half felt that they were at least fairly prepared for a pandemic.

Needless to say, in many parts of the country, the system has been tested to the brink and many organizations, not just in EMS, found themselves struggling to find ways to protect their workforce, manage the ups and downs of call volumes, and distribute rapidly changing information in an organized way. EMS as a specialty rose to these challenges, rapidly adapted and found solutions, but not without paying a significant price in terms of the mental and physical health of EMS professionals.

Tan: If disaster preparedness, to include pandemic response, was important pre-COVID-19, imagine how crucial it is to EMS now. As we continue to learn about the current pandemic, we must learn to adapt those lessons learned to other emerging diseases and other disasters that will challenge our ability to respond.

We also should consider the effect COVID-19 has had on future recruitment. How do we convince the next generation of EMS providers that the risks and hard work are worth it? The EMS Trend Report reveals that it takes 6 to 10 years of service in EMS before the value of patient interaction surpasses other things like adrenaline rush and intellectual stimulation, but we have to get them in the door first.

Zavadsky: The pandemic has dramatically changed nearly every aspect of our culture, and EMS is no exception. The value proposition EMS is transforming, but for the first time in a long time, EMTs and paramedics are being laid off from employment due to decreasing response volumes for traditional EMS services. As we interpret this data, we need to keep in mind that the current economic model for EMS is unsustainable. Prior to the pandemic, it was difficult to empirically prove that what we do every day makes a difference in patient outcomes. But, from a prevention, navigation and public health perspective, the value of our services may be easier to demonstrate that those types of services do actually enhance patient outcomes.

Beermann-Foat: The data also shows that of respondents who said they were planning to leave their current employer, the second most given reason (behind retirement) was to continue EMS employment with another agency. This implies that these people haven’t given up on EMS, but are seeking an organization with a better fit for their needs/wants.

This, combined with the over 50% who said they agreed/strongly agreed that they were optimistic about the future of EMS, shows that EMS is still valued as a profession by those in it. This doesn’t give us a pass to take things for granted and stop our efforts to resolve stressors and challenges that make providing EMS difficult. But it does give us a point of focus to discover why our personnel are leaving our agency to work for another (i.e. pay, benefits, organizational culture, etc.).

Cebollero: EMS is always chasing its tail in retaining high-performing coworkers. From a leadership aspect, we do not need a survey to know we have to change our leadership practice and increase our value in those we need to do the job. The days of command and control, and leading from a position of authority are over. We have to focus on the only organizational resource that increases in value and that’s the workforce.

Cebollero: EMS is always chasing its tail in retaining high-performing coworkers. From a leadership aspect, we do not need a survey to know we have to change our leadership practice and increase our value in those we need to do the job. The days of command and control, and leading from a position of authority are over. We have to focus on the only organizational resource that increases in value and that’s the workforce.

Counts: Retaining personnel means giving them a reason to continue donning the uniform. It means giving them a chance to find joy in work, giving them a purpose, and giving them the flexibility to be who they are while also representing our industry. If we look at the questions about what people find satisfying about working EMS, it’s relieving to see patients and the community at the top of the list. At

the end of the day, we primarily serve our communities by treating patients. If providers don’t value that, they don’t belong, and they likely won’t last.

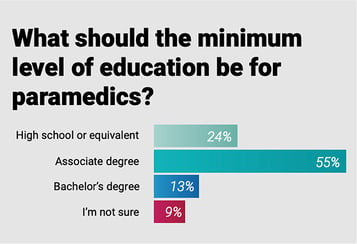

Dorsett: We need to recruit and educate the workforce for the job they are actually going to do, build clinical career paths within EMS, and pay a living wage. Fundamentally, we need to help EMS professionals find value and feel valued for the work that they do.

Dorsett: We need to recruit and educate the workforce for the job they are actually going to do, build clinical career paths within EMS, and pay a living wage. Fundamentally, we need to help EMS professionals find value and feel valued for the work that they do.

Based on the survey results, the more time that someone spends in EMS, the more they value patient interaction and intellectual stimulation, and the less they value the adrenaline rush. This is likely in part something learned through time, but I think it also tells us about those providers who are able to persist in EMS despite low satisfaction with pay and respect; they are a group of people who derive satisfaction out of caring for others, whether it be a rare critical call or the lift assist which they are much more likely to encounter.

The practice of prehospital medicine has transformed in the last 20 years. Most notably, the term “technician” no longer applies to the majority of prehospital providers who function as highly skilled clinicians. Indeed, the term “emergency medical” itself has evolved to include integration of EMS, not just for the management of time-critical conditions, but to the role of EMS as an access point to the healthcare safety net.

EMS has a choice to make: resist change or embrace this expanded identity by changing

the requisite education requirements, focus on integrating within the healthcare system to better navigate patients, demonstrate value to the system, and identify additional reimbursement opportunities to financially support employees.

Tan: Clearly, recruitment and retention of qualified personnel is of major importance to all respondents across all groups. One of the things to note is that as the level of provider education increased, the percentage of providers planning to leave their current employer also increased. Thus, while many of us promote higher levels of education for our field personnel, we must be cognizant of potential unintended consequences of further worsening our ability to retain good people in the field.

As an industry, we must discover the real intrinsic and extrinsic principles that providers value to make EMS a lifetime commitment; and it isn’t salary alone, as the results also demonstrate that as education level increases, the importance of wages and benefits actually decreases. I believe we need to find ways to compensate personnel who advance in education, and we also need to make sure the industry allows for meaningful application of that higher education in the form of additional practice opportunities in areas such as MIH/CP and critical care.

Zavadsky: Field EMTs and paramedics are the backbone of the EMS system, but they are also in high demand in hospitals, clinics, and other healthcare settings. EMS leaders need to invest energy and resources to gain insight into why people stay in EMS, and create environments that retain quality employees. Many EMS agencies conduct exit interviews to see why people leave. What if we invested the same amount of effort on conducting “stay” interviews – learn the reasons that they stay with us – what are the things that bring them the most satisfaction? What frustrates them? Armed with this knowledge, we can help develop a culture people want to be part of.

Download the full 2020 EMS Trend Report here.

About the Author: Kerri Hatt is the editor-in-chief of EMS1. She is responsible for defining original editorial content, tracking industry trends, managing expert contributors, and leading execution of special coverage efforts. Prior to joining Lexipol, she served as an editor for medical allied health B2B publications and communities.

For the latest stats on the state of the EMS profession in 2020, check out part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4 of our 2020 EMS Trend Report coverage.

Although they have the advantage of prior awareness and preparation, large-scale planned events pose unique challenges for emergency management...

For Those Who Love a Good "Oopsie!" At Pulsara, we pride ourselves on enabling secure, HIPAA-compliant communication for healthcare teams. But let’s...

March Recap A New Integration: Improving Data Management, Streamlining Workflows, and Improving Care CoordinationOnly a few days ago, we announced...