Does Your Team Feel Unseen? Close the Leadership Disconnect with 2-Way Communication

Editor's Note: In July 2025, EMS1 and Fitch & Associates released their annual EMS trend survey, What Paramedics Want, proudly sponsored by Pulsara....

EDITOR’S UPDATE: The ET3 program is mentioned throughout the below interview. Please note that, as reported by JEMS.com on 6/28/23, the federal government is ending the ET3 program. According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “This decision does not affect Model Participants’ participation in the Model through December 31, 2023.” Read the full article on JEMS for more details: ET3 Program Comes to an Abrupt End. Be advised that Mobile Integrated Healthcare and Community Paramedicine are separate initiatives and are unaffected by the ET3 program termination.

__

What if you could keep hundreds of low-acuity patients a week from having to needlessly go to the emergency room? With a scalable system of care, Austin-Travis County EMS is doing just that. In just three weeks, they kept 434 low-acuity patients out of the hospital—rerouting them to faster and more appropriate care via their ET3 clinic partner agency and the telehealth communications and logistics platform Pulsara.

Recently, Commander Steve White and Dr. Carlos Navarro presented a webinar to share their experience with creating the C4 unit, walk through a case study, and offer tangible takeaways and cutting-edge insights. If you haven't yet had the chance to catch up on the conversation, check out part 1 and part 2.

Read on to hear from Commander White and Dr. Navarro as they host a Q&A, answering audience questions about their system, how it works, and how its principles can be applied to other organizations.

Jeff Frankel (Moderator):

That was a great presentation by both of you; thank you for that. I'm so glad that you're seeing success with your ET3 program and hope it can be replicated. We have a lot of questions from the audience, so let's dive right in.

Steve White:

All right, let's take some questions, and we'll try to give some answers.

Q: If the receiving facility is not an ET3 destination, how do they participate in the ET3 model? Or is there a different option you're exploring through a partnership with that facility?

Steve White:

Yeah, the ET3 does have a partnership agreement that's extremely specific. We have gone beyond that because equity is very important in my community, with my city council, with my department leadership, that we are able to offer the same service to everyone regardless of age, or whatnot. So, we were able to set up partnership agreements outside of ET3 because we have these equity requirements. We have found these partnerships not only just by going out and getting them to participate, but also because, for instance, we've run into a situation where we needed a walker, and we just started beating the bushes, looking for a walker to provide for this patient. It's that kind of tenacity that gets you these relationships.

That's how we got Post Acute Medical; that's how we got Hospice. Basically, a situation would present itself where we had a need, and we would start trying to fill that need. We would consult other resources inside the city. We have community health paramedics and mental health professionals, and so we would ask them, who can we call? Who can we ask? And it's through those interactions that we've built up these relationships.

Q: Earlier you mentioned you have 300+ people who have been offered telehealth. Our questioner is curious to know: how many people have accepted and followed through with the telehealth service?

Steve White:

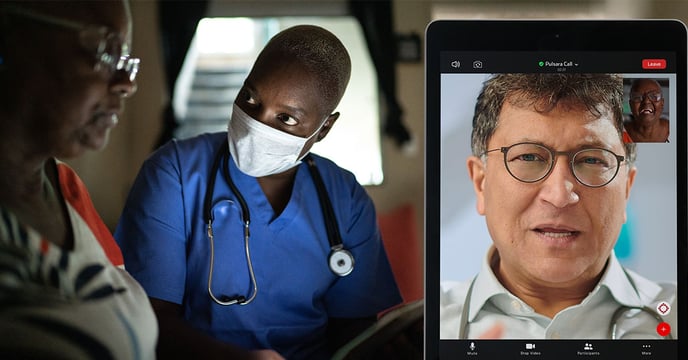

Yeah, we do telehealth a little bit differently, and actually, it's forever evolving. I have the luxury of having access to fantastic medical direction. They are very involved in this program, and they participate in this program. When I talk about treat-in-place options, I can literally send a physician for sutures. I can send a physician for PEG tube replacements or for Foley replacements. I can send a physician on-scene for whatever treat-in-place pops up. But it is also our medical directors that are providing our telehealth services right now. And we do our telehealth services just like we do with Dr. Navarro when we are transporting to his clinic. We're doing them on Pulsara. And what that allows us to do is when that medical director pulls up the Pulsara notification, they can see the vital signs, they can see the EKG, it's very visual for them. And then through the video feature, they can see the patient themselves.

So we have an internal telehealth. The problem that we've run into with this last COVID wave is that once the crews bought into this concept that not everyone had to go to the emergency room, the response was overwhelming. My medical directors were up 24 hours a day, 7 days a week answering Pulsara and phone calls for telehealth consultation. It's to the point now where at some point we're exploring an external telehealth option. But when you talk about consent into the telehealth option, that video feature is significant. The ability to see the doctor has a significant effect on the patient. And then the doctor's ability to see the patient gives them a comfort level that's really important.

Q: Are bedbound patients accepted into clinics? And if so, are ambulances tied up for transport to bring them back home?

Steve White:

So we do not—what do they call it? Turn and burn? Where you take the patient to the clinic, you wait for an evaluation, and then you bring them back. When we do an alternative transport, we treat it just like we would a 911 call, which means we'll take you there, and then a 911 ambulance is not going to come back and pick you up. Now if we do transport a bedbound patient to Dr. Navarro's clinic or any one of our other partners, a non-emergency ambulance can come pick them up and take them back. Part of the logistics is that most of the time, those questions have to be answered before you transport to the clinic, because the patient is going to be asking, "How do I get home?"

When you're telling them, "We're going to take you to the clinic, and we're going to let you see your doctor that knows all about you," and you have that conversation on the phone, they're going to ask, "How do I get home?" The emergency rooms have a pretty good system, whether it's cabs, Ubers, or non-emergency ambulances that will be transporting them back. And so we kind of glean off of that; we take the model that they use, and we use it as well.

Q: How does the ambulance crew know the patient is part of the WellMed PCP/clinic?

Steve White:

Okay. This was a hard challenge and continues to be. In my community, we have several large clinics and payer networks, health care networks. We have searched high and low for a technology solution to this. But literally, it comes down to picking up the card, looking at the logo, and seeing that they are a WellMed patient. Just starting large and saying they are a Medicare patient or they're a Medicaid patient, or they are private pay, or we have our MAP funding here, which is the county-assisted health insurance. It really takes picking it up and looking at the card. Now with our health record software, once you put their billing information in, if you put their insurance information in and you've run on them a second time and you pull them up, that information will be there as well.

But it does take an education component to say, this is offered through WellMed. WellMed is a potential client. WellMed is one of our partners, and to have the crews look for that. Now, one of the other aspects is because of our partnership with WellMed, sometimes we'll get into a situation where one of our patients needs primary care. They have not established primary care. And so at that point, we're able to refer them to WellMed and say, call this phone number if you need primary care. We can give them a list of three or four different places to call for primary care. But it does make it a lot easier to try to get them on the right track with primary long-term care.

Q: What happens when the patient who would qualify for patient status is not a patient in the clinic system?

Steve White:

I'll let Dr. Navarro answer this because it happened—two weeks ago?

Carlos Navarro:

Yeah. So just to clarify, the question is, what happens if there's a patient that's not part of WellMed that gets transported to one of our clinics?

Jeff Frankel:

Yeah, that's it.

Carlos Navarro:

So it actually happened. Part of the reason when we were putting the program together is exactly that scenario, right? We want to make sure that the patient has a good experience, whether they are our patient or somebody else's patient. So having that layer there where the Pulsara notification comes in with the patient information, we can check on our computer system—EMR—to see if they are really part of our clinic or not. And we can direct the crew on the scene and tell them, "Oh, sorry, that's not one of our patients." In this particular scenario, there was one patient that belonged to one of our providers that was not at that particular clinic, but part of WellMed. So we ended up seeing the patient anyway, treating them, and getting them follow-up with their primary care provider that was assigned. They hadn't met their primary care provider. A lot of patients sign up for insurance and don't even know who they are assigned to, right? So this was the case with that patient. They didn't know who to go to, they just needed help. And we were able to provide that assistance and get them situated.

Q: There is data suggesting that paramedics are not particularly good at determining who should or should not go to the ED. Have you found this to be true? Also, will you be publishing any literature on your experience?

Steve White:

Yeah, this is a great question. And so the way that we have addressed this is that we've put multiple layers into the system. The first layer is that the 911 call is actually triaged by EMTs in our department. They are certified. That's your first layer. The second layer is the C4. Now, the C4 has had extensive training, training beyond a regular field crew, in what we call "red flags." Red flag training is provided by our medical direction, where they address the things that can kind of come back and bite you if you don't pay attention to them. Those are the things that will sneak up on you because you might see it as something pretty minimal, but in actuality, it's something that could be life or death.

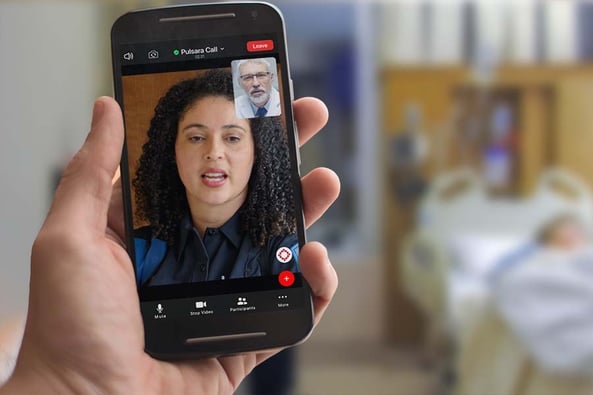

And then the third thing is, there is not a decision made about whether you go to the hospital or not with treatment-in-place. We're not talking about your standard patient refusal. And there's no alternative transport that doesn't start with telehealth, right? So the final layer that we use to protect ourselves and our patients is that everything starts with a conversation with the doctor. If we're going to go to Dr. Navarro's Clinic, our conversation is with him. If we're going to transport to a pain management clinic, that's going to start with a conversation with our medical directors. I don't know if y'all can tell from this conversation, but we keep our medical directors extremely busy.

And the other thing that has come up out of this that's very interesting, is that this model also works very well with high-risk refusals. You have someone to call to provide some sort of resources, whether it's telehealth or anything that could be considered treatment-in-place. Where formerly, if you had a patient that was a high-risk refusal that would not go to the hospital when they needed to go to the hospital—you may have encountered this with your COVID patients over the past year and a half. There is a fear, especially for elderly COVID patients, of going to the hospital and dying in the hospital. And they are so averse to that.

In this model, you are able to provide them with some sort of treatment. Where normally, you would get the high-risk refusal, you would leave, and the outcome...who knew. With this model, you can now do a telehealth call, you can prescribe medications, the C4 will facilitate those medications being delivered to you, or will go pick them up themselves. And we have a follow-up system that maybe you don't have in your department right now.

Any call, whether it's a high-risk refusal, whether it's a treat-in-place, whether it's a telehealth, has the opportunity now for a medical professional to follow up with them. All you have to do is call the C4 and say, "This guy is going to need a follow-up." So we've tried to build in as many layers of protection as we can into the system.

And as far as are we going to publish the works? Yes, our office of the Chief Medical Officer, which is our medical direction here in Austin, Texas, is going to write a paper on it. I'm sure they'll be published; they're very good authors, they are very smart people.

Q: Do you run this 24/7? And how is this billed?

Steve White:

During a crisis, we are 24/7. Now, in between crises, we operate from 7:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. The best thing about this team is that it's like breathing: you can expand it out and you can shrink it back depending on what the situation is. If we have another hurricane or another ICE-pocalypse, we can breathe out quite easily. We try to keep people trained up that may not be assigned full time to the C4. We keep them trained up, keep them participating, and we have a couple of different ways to make that happen so that if we need to bring them in, their spin-up time is very short. The thing about the C4 and what we're doing is, it changes so fast. It changes directions on a dime. And so you have to keep the education up. It's very, very important.

Q: Speaking of C4's, who staffs them? And are they doing other tasks, with only 10 patients a day?

Steve White:

The C4 is currently staffed with clinical specialists. Clinical specialists are paramedics in our system, and it is their full-time job. They are assigned there. They do not have split assignments. Then we have people that we have trained up that work in the field. And they'll come in and help cover shifts and whatnot. The team does a lot. It does all of the treat-in-place models, and they do all the follow-ups. And then they also handle a lot of the COVID aspects of our department and of our city. So they have a really big job. It's pretty busy up there, especially in a crisis. If we have a COVID wave, it's pretty nuts.

Jeff Frankel:

I bet. So that's all we have for today. I want to thank you again to our viewers for joining us today and to our sponsor, Pulsara. Everyone, thank you so much for attending today. Commander White, Dr. Navarro, I'll give you guys a chance to offer any final words.

Steve White:

I really think that this is the future. The "you call, we haul" era has ended. It's definitely different than when I got into this. We really have started to accept our position in the health care system, where it's not going to be just about taking people to the emergency room. A large chunk of what we deal with is going to have to have another option.

We received many great questions during the webinar and unfortunately did not have time to cover all of them live. Here are the rest of your questions, answered by Commander White, Dr. Navarro, and Team Pulsara!

Q: What about patients that are new to WellMed or uninsured?

Answered by Dr. Navarro: We are always happy to accept new patients, but not during an acute EMS call. Those patients are given a contact number to enroll with WellMed and get a routine appointment after the acute event is resolved.

Q: Are there Licensed Clinical Social Workers involved in the program? Do they go into the field, or work in a PCP office?

Answered by Dr. Navarro: WellMed has social workers that are available to all our members, and they are able to make home visits.

Q: How do you get your medics and supervisors to buy into the ET3 program?

Answered by Steve: The obvious answer to this is a culture change. So then the question becomes, how does a department instill a culture change? Let’s dive into the decision-making of a paramedic. ET3 presents a conflict for a field provider. Years of conditioning and expectation has reinforced the idea that if a patient calls 911, the only option is transport to the Emergency Room. When a paramedic encounters a low-acuity ET3 patient, the internal battle begins. The paramedic has to make a choice they are comfortable with. In order for ET3 to be successful, the paramedic has to know that TIP (treat-in-place) or alternative transport is acceptable and/or expected. The message from operational and medical leadership has to be strong enough to make the paramedic comfortable with their decision. Field supervisors and training officers are the messenger.

When dealing with the ET3 program, I have seen two successful approaches:

My experience falls into the first category: a slow grassroots culture change that is still developing. Paramedics are a unique breed. In my experience, they have two main motivators. The first overarching motivator is that paramedics want to do the right thing. The second is time management.

Paramedics are efficient creatures. They are part clinician, part engineer, part mad scientist. I challenge you to find a profession that can use head blocks or Coban in more creative ways than in EMS. At the core, paramedics are problem solvers. They are the real MacGyvers of the medical community.

Make ET3 successful by playing to these character traits. TIP is tool that makes a paramedic more efficient. Flight line training at hospitals has been very successful for our department, but having a positive experience with TIP has been the biggest success. We have targeted a specific hospital with flight line training during hospital hold times, and seen an instant increase in TIP participation. TIP plays to a paramedic’s strengths by saving time and doing what is best for the patient. Taking partner agencies out to meet crews has helped as well. Paramedics need to understand their greater role in the medical community.

Mandatory compliance will change the culture faster, and has greater accountability. The field providers are given training in ET3/TIP and defined expectations are set. This requires a way for the expectations to be tracked and then the provider has to defend their decision to use or not use the ET3/TIP option.

The ideal would be a combination of both methods. Start the ET3/TIP program with a slow grass roots campaign to introduce the concept and work out any workflow issues. Progress the program into defined expectations that can be tracked and defended. At that point, it is now a part of everyday life—the same as a Trauma Alert or a STEMI Alert.

Q: Are there criteria a patient has to meet to rule in/out, or is it purely at the discretion of your crews?

Answered by Steve: Every paramedic/EMT understands the concept of sick/not sick. It is the view from the door, the scene size up, that dictates the pace and urgency of the call. We have adapted that concept to ET3/ TIP. Hospital or no hospital? If a provider thinks the patient complaint does not require a hospital, that is step one. Our department has over 600 field providers, and keeping everyone up to date on what TIP is available is an impossible task. We opted for a model where a small group is specifically trained to know what resources are available, and the field provider calls for a consult. Together, the field provider, the patient, and the consult decide what the best course of treatment is. Each TIP does have inclusion/exclusion criteria. Age, medical history, vital signs, living conditions, and communication are all parameters we look at. Follow up after a TIP is extremely important, and we have to be able to contact the patient in some way. Transportation plays a large role as well. Each situation is different, and because it is a collaborative effort between several providers, it makes the paramedic and the patient more comfortable with their decision.

Q: Do you default to an ED at 0200 hours, for example, when alternative destinations are closed?

Answered by Steve: We have operated within two different hours of operations. When staffing allows, our consult team is on 24 hours a day; currently, we operate from 7:00 am to 10:00 pm. The majority of alternative destinations are closed by 9:00 pm. Very few pharmacies are open 24 hours. Medical and mental telehealth is available 24 hours a day and is handled through medical control after the hours of 10:00 pm. An overnight TIP will be referred to the consult team for follow-up the next day.

Q: Would it be possible to combine 3 health systems into one "tool" like Pulsara? For example, in Tulsa, there are St. Francis, Utica Park, and Ascension health systems. Would you be able to choose a system to connect into on scene?

A: Yes, absolutely!

Q: What does the transition between ED Medical Direction to other welcoming transport facilities. If EMS responds and it is cleared through Online Medical Control that the patient is more appropriate for another facility, does the call act as documentation of that referral? Are the calls recorded as legal documentation of transfer of care?

A: Yes, every keystroke is recorded and a final record can be exported, printed, or pulled at any time. The crew will obviously still complete a PCR but everything in the Pulsara app is recorded.

Q: What software and management do you use for your telemedicine system?

A: The Pulsara platform is the backbone for Austin-Travis County EMS's telemedicine system, and the medical control docs are currently staffed through Austin-Travis County EMS.

Pulsara is helping with COVID-19 management by helping mitigate patient surge, streamlining patient transfers, minimizing exposure, and more. Learn more about COVID-19 + Pulsara here.

Editor's Note: In July 2025, EMS1 and Fitch & Associates released their annual EMS trend survey, What Paramedics Want, proudly sponsored by Pulsara....

![[PRESS RELEASE] Published Research Finds Up to 31% Faster STEMI Treatment Times in Rural Hospital Setting with Pulsara](https://www.pulsara.com/hubfs/_1_website-page-blog-assets/pulsara-hosp-teams-assign-cardio-stemi-rn-1200x701.jpg)

Published research shows how using Pulsara, alongside standardized field activation and a focus on stakeholder relationships, improves STEMI care and...

Editor's Note: In July 2025, EMS1 and Fitch & Associates released their annual EMS trend survey, What Paramedics Want, proudly sponsored by Pulsara....